Over the last few years, you all may have noticed that The Great Southern Brainfart has grown a bit. Not only we continue to bring you all the hard rock, classic rock, metal, and all other things but as you all may have noticed, artists such as Jellyfish, Walking Papers, and Styx just to name a few have found a home here. Why? Because I love all kinds of music and I really wanted this blog to become a platform that would break the boundaries of what people think this blog should be.

This post couldn’t be a better example of this. Many may not know but I was a folksinger/songwriter on my own for the better part of 15 years or so and have since fronted a few roots rock bands so my folk influence is always going to be there. It’ll never go away. My dear friend Katie Flannery from the Metropolitan State University of Denver asked if I’d be willing to share this story she wrote about the legendary Pete Seeger and I am more than honored to have Katie’s piece on my site!

===============================================================================

Disturbing the Status Quo: Pete Seeger at 100

Disturbing the Status Quo: Pete Seeger at 100

Katie Flannery, April 2019

The songs of Pete Seeger surrounded me during my childhood: “If I Had a Hammer,” “Little Boxes,” and “Turn, Turn, Turn.” I didn’t know what these songs meant – all I knew was that they were catchy and fun to sing. As I grew older and dove into the study of American music and important American musicians, my re-discovery of Pete Seeger and his music touched my soul. His importance in folk music looms large and his role as a social activist is legendary. He was brave in a time when many were not: during the anti-Communist hysteria of McCarthyism and the Red Scare. As we celebrate the 100th anniversary of Pete Seeger’s birth on May 3rd, it is important to look carefully at his music and to realize that he may be gone, but his generation-spanning message still resonates today.

Early Days and The Fight for Social Change

Pete Seeger was born into a musical family: his father, Charles, founded the musicology program at the University of California, Berkeley, a position from which he was fired in 1918 due to his pacifist views. His mother Constance was a concert violinist and instructor at the prestigious Julliard School of Music. When he was seven, his parents divorced, and his father married Ruth Crawford – now considered to be one of the most important modernist composers of the twentieth century. She had a great love of folk music and became a folk music specialist – something that Seeger and his step-siblings absorbed. He attended Harvard University but lost his scholarship after he failed a test, so he dropped out of school and he spent time living the vagabond life: jumping rides on freight trains and hitchhiking across the country. He then went to New York City to work for Alan Lomax at the Archives of American Folk Music. His father’s viewpoints regarding politics were influential to Pete and it was then that he coalesced his own radical political perspectives.

He focused on song writing and by 1940 he had formed the Almanac Singers along with Millard Lampell, Lee Hayes, and Woody Guthrie. This New York City based group was only together from 1940-1943 but dominates the history of American folk music. The group sang

topical songs and used their performances to address fascism and advocate for anti-war, anti-racist, and pro-union causes. According to Lampell, the Almanac’s creed was a simple one:

Our work is to be performed in the manner which best aids the working class in its struggle to claim it’s just heritage. We just stick to the old tunes working people have been singing for a long time—sing `em easy, sing `em straight, no holds barred. We’re working men on the side of the working man and against the big boys.

The Almanac Singers were committed to radical political action and advocated for unionizing and fair wages. One of their best-known songs is “Talking Union” from 1941 and was written by Lampell, Hays, and Seeger. This song is commonly known as a ‘talking blues’: more of a rhythmic recitation of a poem or a story and not sung in the traditional sense. The text includes lines such as:

If you want higher wages, let me tell you what to do;

You got to talk to the workers in the shop with you;

You got to build you a union, got to make it strong,

But if you all stick together boys, ‘twont be long.

You’ll get shorter hours,

Better working conditions.

Vacations with pay,

Take your kids to the seashore.

It ain’t quite this simple, so I better explain

Just why you got to ride on the union train;

‘Cause if you wait for the boss to raise your pay,

We’ll all be waiting till Judgment Day;

We’ll all he buried – gone to Heaven –

Saint Peter’ll be the straw boss then.

Now, you know you’re underpaid, hut the boss says you ain’t;

He speeds up the work till you’re ‘bout to faint,

You may he down and out, but you ain’t beaten,

Pass out a leaflet and call a meetin’

Talk it over—speak your mind—

Decide to do something about it.

‘Course, the boss may persuade some poor damn fool

To go to your meeting and act like a stool;

But you can always tell a stool, though—that’s a fact;

He’s got a yaller streak running down his back;

He doesn’t have to stool—he’ll always get along

On what he takes out of blind men’s cups.

Communism and the House Un-American Activities Committee

In 1942, Seeger was drafted – and also joined the Communist Party. While he was on leave he would still perform with the Almanac Singers and sing songs such as “The Sinking of the Reuben James,” which is about the first U.S. cargo ship that was torpedoed and sunk by a Nazi U-Boat, and songs that chronicled the exploits of volunteers who fought in Spain against Franco’s fascism during the Spanish Civil War. Pete said of the Almanac Singers:

We were a strange combination of people and we put out some good songs and lived through exciting times. We participated in these exciting times . . . we called ourselves Communists. Probably none of us agree even now exactly on the definition of Communism. But I don’t think any of us are ashamed of what we did way back in the days of 1941 and ’42.

In the army, Seeger was serving his country and fighting fascism. After the war, things became difficult for anyone that had beliefs similar to his. A mania of anti-Communism swept the country and anyone that was a Communist, leftist, or liberal were subject to legal and economic punishment. As a result, Seeger was blacklisted for two decades: he was not allowed to appear on major network television stations and commercial radio stations refused to play his music. Not only was it a financially troubling time for him, but the threat of going to prison for contempt was a constant reality. On March 29, 1961, Pete Seeger was found guilty on ten counts of contempt of Congress. This conviction was the result of a ten-year long investigation of his communist ties with his organization called People’s Songs – a group that published labor and folk music. While testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1955, Seeger didn’t invoke his Fifth Amendment rights, but what he called his First Amendment rights: the right to free speech and to challenge the committee’s right to ask questions about his or anyone’s political activities. He said:

I am not going to answer any questions as to my association, my philosophical or religious beliefs, or my political beliefs, or how I voted in any election, or any of these private affairs. I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this.

He did offer to sing “Wasn’t That a Time,” mentioning that it probably wouldn’t sound as good without his banjo. He refused to answer any questions regarding the specific instances the committee was interested in. He insisted:

I have sung for Americans of every political persuasion. . . no matter what religion or color of their skin, or situation in life. I have sung in hobo jungles, and I have sung for the Rockefellers, and I am proud that I have never refused to sing for anybody. That is the only answer I can give along that line.

The practice of invoking the First Amendment defense was not constitutionally protected and he knew that he could be separately charged for each of the questions he refused to answer. Over six years, Seeger would be indicted, tried, and convicted. He was sentenced to one year in prison for each count. His conviction was ultimately dismissed in 1962 due to technicalities regarding the HUAC’s investigative powers.

An event that happened in September 1949 may have deeply affected him even more so than the Congressional hearings. His car and over a thousand other cars were stoned by right-wing anti-Communists as they left a performance in Peekskill, NY. Even more than sixty years after the event, Seeger would mention the Peekskill riot in interviews and comment on the fact that he had a first-hand look at what a fascist world might really mean, and he used it as a reason for never giving up his political work. He survived that night and the Congressional hearings and wrote an essay titled “The Theory of Cultural Guerrilla Tactics” which summarized what he attempted to do during the 1950s and how he hoped his work would continue. He recorded and composed the music for “Where Have All the Flowers Gone” and helped bring attention to “We Shall Overcome” and “Little Boxes.” He traveled across the country and played where ever he could, including some legendary performances at college campuses in the 1950s and into 1960.

Probably one of the most important and fabled performances of Pete Seeger’s career happened in 1968 when he appeared on the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour on CBS. The end of his blacklisting was a performance on the show a year prior when Tom and Dick Smothers convinced CBS to allow Pete Seeger to perform on the show. The brothers were no strangers to conflicts with the censors on the network television channel and knew that having Seeger appear on September 19, 1967 would ruffle some feathers. The censors asked him to omit the last verse of the song “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy.” Seeger refused and sang the song in its entirety. CBS then cut the whole song from the broadcast. He was outraged. “I’m very grateful for CBS for letting me return to commercial broadcasting,” he said to the New York Times, “but I think what they did was wrong, and I’m really concerned about it. I think the public should know that their airwaves are censored for ideas as well as for sex.”

“Waist Deep in the Big Muddy”

“Waist Deep in the Big Muddy” is an anti-war song written in 1967 and tells the story of a platoon fording a dangerous river in Louisiana on training patrol in 1942. The captain ignores his sergeant’s concerns as the water level rises from their knees to their waists as “the big fool says to push on.” The captain orders the platoon to continue when suddenly they are up to their necks and the captain drowns. The sergeant orders the men back to shore and they escape the Big Muddy. Seeger’s performance of the entire song on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1968 was broadcast into the homes of millions of viewers. Seeger’s performance was intense as he stared directly into the camera. He energetically tapped his foot to the beat and his performance gradually became emotional with flashes of anger on his face and an occasional rough and growling timbre to his voice. This was a significant and triumphant moment for Seeger after the long years of the blacklist. There is no mistake that the listening audience in the late 1960s would have understood the parallels to the Vietnam War with the lines:

Well, I’m not going to point any moral,

I’ll leave that for yourself.

Maybe you’re still walking, you’re still talking,

You’d like to keep your health,

But every time I read the papers, that old feeling comes on,

We’re waist deep in the Big Muddy

And the big fool says to push on.

Waist deep in the Big Muddy,

The big fool says to push on.

Waist deep in the Big Muddy,

The big fool says to push on.

Waist deep, neck deep,

Soon even a tall man will be over his head.

We’re waist deep in the Big Muddy,

And the big fool says to push on.

Seeger recounted his experience on the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour by saying:

“Of course, a song is not a speech, you know. It reflects new meanings as one’s life’s experiences shine new light upon it . . . often a song will reappear several different times in history or in one’s life as there seems to be an appropriate time for it. Who knows?”

Contemporary listeners can make the parallels to current events: the Black Lives Matter and Me Too movements, civil rights for all people, climate change, wars around the world, and the burning of fossil fuels. The message of this song is just as timely today as it was in 1967.

Seeger knew that music is not static – it has been employed for many different purposes throughout history. In a 1971 interview he said:

“Music has been used throughout human times in many ways, sometimes to support the status quo, sometimes to disturb the status quo. Music has been used in religion, in war, in politics and love. It is only recently that music has been thought of as mere entertainment. In previous centuries, man needed music to help him get through life. Whole villages sang their songs together, confirming the fact that they were members of that village, and when they danced and sang together, it reinforced their strength as a community of people. I’m sorry when people think that music is just something to escape their troubles. As best, music helps in understanding troubles and helps get people together to do something about their troubles.”

Keeping the Legacy Alive

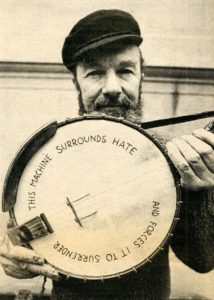

On Pete Seeger’s banjo was printed: “This Machine Surrounds Hate and Forces It to Surrender.” He intended to use music as a force to facilitate social change. He wanted to help people to do something about their troubles. To be active and change society. He urged young people to spread his messages to new places and to new generations. He implored to the young people to use their guitars and voices to, “plant the seeds of a better tomorrow in the homes across our land. . . they are creating a new folklore, a basis for a people’s culture of tomorrow. For if the radio, the press, and all the large channels of mass communication are closed to their songs of freedom, friendship and peace, they must go from house to house, from school and camp to church and clambake.”

More than anything, Seeger wanted his audiences to sing along with him – not to just merely be passive listeners to the music. He not only was a performer, but a teacher. Who will take up his mantle? The next Pete Seeger does not have to be a performer of “folk music.” Seeger never made the mistake of labeling himself as a folk performer. He said he played the music that worked for the task he wanted to accomplish – no matter the official genre. His legacy is visible in the punk rock scene when lyrics are about surviving as a transgender woman, or in creative collectives where progressive poetry about civil rights are married to movement and visual art. His legacy is heard in multiple songs of Kendrick Lamar, it’s heard in the powerful song “This is America” by Childish Gambino. It’s heard in rap and hip hop as the performers rhyme about police brutality and the murders of Black men and women. It may not be the same style of music that Seeger performed, but it is familiar music to today’s young people and it transmits the message of participation, solidarity, standing up in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds, and a call to action. Just the type of message to stir up the status quo.

Katie Flannery is currently musicology faculty at the Metropolitan State University of Denver where she specializes in American popular music. She is a freelance writer and an active contributor to journals, magazines, and blogs.